Flexible language

I’ve been learning Lisp for few years now, and every Lisp book I read keeps saying that Lisp is a flexible language that you can extend to the degree when it fits naturally to your domain. It’s easy to say, but what exactly does this phrase mean? After all, when you program in your non-Lisp language, don’t you modify it for your domain problem? I’ve been thinking about it for a long time, and only recently I started to understand what flexibility really means. There is a difference between using the language and changing the language to solve a problem. In this post I will try to show the difference based on a simple example.

Problem

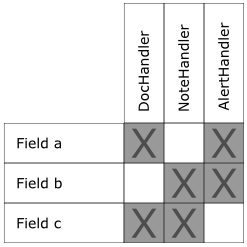

Suppose you have a process that listens to a message queue. The messages are just ordinary maps. If the map contains certain keys, one or more handlers must be invoked. Here is a matrix that shows which handler is invoked for which key.

For example, if the map has key a, then DocHandler and AlertHandler need to be called. If it has key b, then NoteHandler and AlertHandler are called. In reality there might be more keys and more handlers, but for simplicity we limit our example to three keys and three handlers.

Java

Let’s see how this can be implemented in Java. I chose Java just as an example of non-Lisp language. You can pick any other non-Lisp language instead.

public class SimpleMessageListener {

public List onMessage(Map message) {

List result = new LinkedList();

if (isDoc(message)) {

result.add(handleDoc(message));

}

if (isNote(message)) {

result.add(handleNote(message));

}

if (isAlert(message)) {

result.add(handleAlert(message));

}

return result;

}

// Decision makers

private boolean isDoc(Map message) {

return message.containsKey("a") || message.containsKey("c");

}

private boolean isNote(Map message) {

return message.containsKey("b") || message.containsKey("c");

}

private boolean isAlert(Map message) {

return message.containsKey("a") || message.containsKey("b");

}

// Handlers

private String handleDoc(Map message) {

return String.format("Document:%s:%s", message.get("a"), message.get("c"));

}

private String handleNote(Map message) {

return String.format("Note:%s:%s", message.get("b"), message.get("c"));

}

private String handleAlert(Map message) {

return String.format("Alert:%s:%s", message.get("a"), message.get("b"));

}

}The internals of handle methods might be very different in reality. Consider the fact they have the same structure here as a coincidence. What is not coincidence though is the structure of is methods. Those methods are identical indeed.

Is this code clean? I would say, no. The main issue is that it’s split in three separate but closely related parts. If tomorrow I introduce another message key and a new handler, I have to change three places in the code. Another problem is the code duplication in two spots: a series of if statements and a group of is methods.

The last thing to notice about this code is that it’s hard to see what kind of problem it’s trying to solve. If I didn’t provide a matrix which maps message keys to handlers, it would take even more time to figure out what the code is doing.

Can we make this code better? Let’s rewrite it as follows:

public class FunctionalMessageListener {

private interface Handler {

void handle(Map message, List acc);

}

private class DocHandler implements Handler {

private boolean isDoc(Map message) {

return message.containsKey("a") || message.containsKey("c");

}

public void handle(Map message, List acc) {

if (isDoc(message)) acc.add(String.format("Document:%s:%s", message.get("a"), message.get("c")));

}

}

private class NoteHandler implements Handler {

private boolean isNote(Map message) {

return message.containsKey("b") || message.containsKey("c");

}

public void handle(Map message, List acc) {

if (isNote(message)) acc.add(String.format("Note:%s:%s", message.get("b"), message.get("c")));

}

}

private class AlertHandler implements Handler {

private boolean isAlert(Map message) {

return message.containsKey("a") || message.containsKey("b");

}

public void handle(Map message, List acc) {

if (isAlert(message)) acc.add(String.format("Alert:%s:%s", message.get("a"), message.get("b")));

}

}

private List<Handler> handlers() {

return Arrays.asList(new DocHandler(), new NoteHandler(), new AlertHandler());

}

public List onMessage(Map message) {

List result = new LinkedList();

for (Handler handler : handlers()) {

handler.handle(message, result);

}

return result;

}

}In this version we eliminated ugly if series, and grouped together decision making logic and message handling. From that perspective the code became cleaner, but not necessarily clearer. Now it actually takes more effort to understand what the code is doing. Also, the duplication inside the is methods is still there. We can fix it by extracting it to some abstract class or utility method. We can also use Java reflection within handlers method to build a collection of handlers without explicitly specifying them. All these manipulations arguably make the code cleaner, but… one thing we’ll never be able to fix is the separation between decision making logic and message handling. Whatever you do, there will always be the if-statement, in one form or another, that checks if you need to process the message, and the message processing logic itself. Those two things will always be separate. This is the point where we hit the language limits.

Clojure

Now let’s try to solve the same problem in Lisp and see if we can fix the language to eliminate the last issue from the paragraph above. Here is the direct translation of the previous Java snippet to Clojure dialect of Lisp

(defn- doc-handler [msg]

(let [a (msg :a), c (msg :c)]

(when (or a c)

(format "Document:%s:%s" a c))))

(defn- note-handler [msg]

(let [b (msg :b), c (msg :c)]

(when (or b c)

(format "Note:%s:%s" b c))))

(defn- alert-handler [msg]

(let [a (msg :a), b (msg :b)]

(when (or a b)

(format "Alert:%s:%s" a b))))

(defn- handlers []

[doc-handler note-handler alert-handler])

(defn on-message [msg]

(letfn [(handle [acc h]

(if-let [res (h msg)]

(conj acc res)

acc))]

(reduce handle [] (handlers))))This code is already easier to read, but we can do even better. The separation between decision making logic and message handling is still there. At this point we should ask the question: what kind of code do we want to see there? And the answer is: we want to replace the -handler methods above with the following code

(handler doc [a c]

(format "Document:%s:%s" a c))

(handler note [b c]

(format "Note:%s:%s" b c))

(handler alert [a b]

(format "Alert:%s:%s" a b))You see: no conditionals. Handlers are self-sufficient entities which know when they have to be applied and how. In their signatures they explicitly declare which message keys they expect, and in the body they just use those keys. No boilerplate: clean and simple. The beauty of Lisp is that you can actually implement that code. The way you do it is by creating a macro which generates the appropriate functions. Creating a macro is not a simple task, I spent quite some time to get this one working, but it’s worth of doing, because it makes the code clean and clear.

We can make one additional step further by moving the handler declarations inside the build-handlers function. (We need one small macro for that.) And here is the final solution

(defmacro handler [name args & body]

`(fn [~'msg]

(let [~@(interleave args (map (fn [x] `(get ~'msg ~(keyword x))) args))]

(when (or ~@args)

~@body))))

(defmacro build-handlers [& body]

`(defn- handlers []

[~@body]))

(build-handlers

(handler doc [a c]

(format "Document:%s:%s" a c))

(handler note [b c]

(format "Note:%s:%s" b c))

(handler alert [a b]

(format "Alert:%s:%s" a b)))

(defn on-message [msg]

(letfn [(handle [acc h]

(if-let [res (h msg)]

(conj acc res)

acc))]

(reduce handle [] (handlers))))As I said, the first macro might be cryptic, but look at the lines 11–20. This is the essence of our problem, and it cannot be done any simpler. Suppose, we need to implement a new handler which should be called if key c is present in the message. Here what we would need to add to build-handler’s body to implement this new requirement

(handler new [c]

...)Simple, right? And what if a new key d is added to the message that should be processed by document handler? Here is what we need to change

(handler doc [a c d]

...)We just add a new key to the function’s parameter list. That’s it — one-word change.

Summary

Lisp is the most powerful programming language. By that I mean you can change the language in such a way that the solution to any particular problem can be expressed in the simplest possible way. By changing the language, you can remove all the barriers between the language and the problem domain. I hope I demonstrated this in my simple example.

Resources

Clojure source code for this blog, along with the unit tests.